This Digital British Islam archive represents a compilation of selected Mosques and mosque organisations from across the UK’s geographical spread as well as ethnic, cultural, religious and social markers from within Britain’s diverse Muslim communities.

The content within these websites can tell us something about their respective institutions and organisations. For larger mosques, websites act as comprehensive community portals for a number of services. In terms of religious services these include prayer and prayer-related activities, as well as information about fatwa and religious guidance services, and the booking of religious rites including marriage and funeral services. Larger mosques also offer social and community support operations and often these are more prominently highlighted on their websites. For instance, the Cambridge Central Mosque foregrounds regular mosque activities but also has links to podcasts, guided tours, the mosque’s gardens and café, as well as prominently highlighting its eco- focus. The website design is professional and aesthetic, organised by theme, and though extensive in content, it is easily navigable.

This is in contrast to smaller mosque websites where the design is more basic and sometimes rather amateur. For some of the smaller bodies, the website largely represents a digital placeholder. Websites for smaller local mosques can often be very simple and limited in the content they offer – giving location and contact information, local prayer timetables and perhaps hosting a donations button.

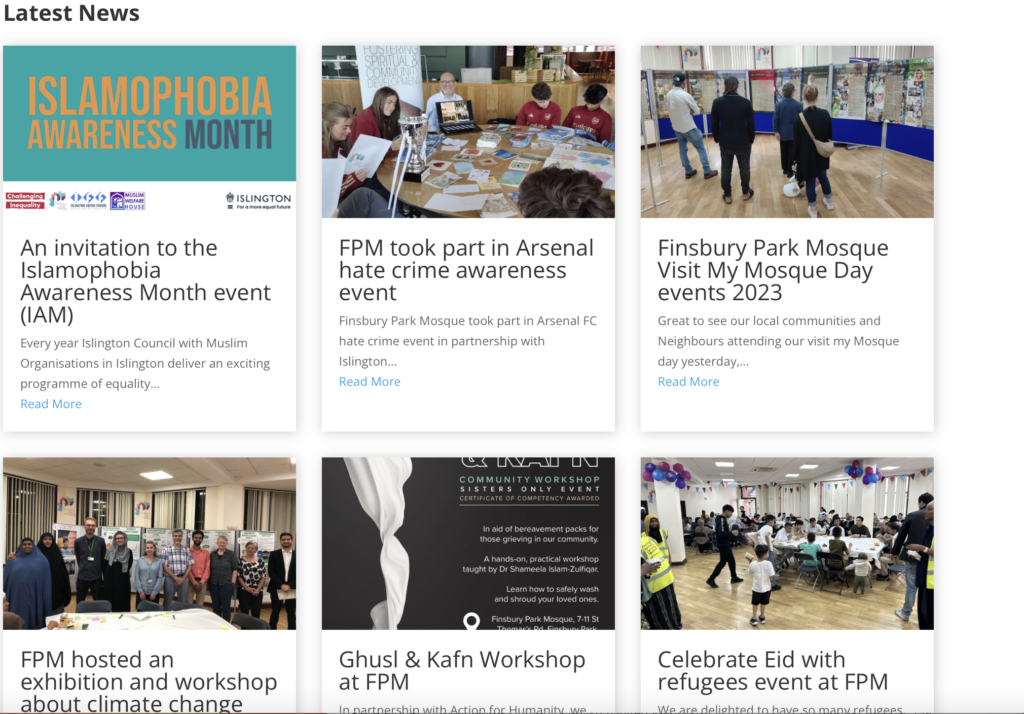

For the more sophisticated websites, a common theme is an emphasis on community outreach. Many of the sites profiled here foreground ‘open house’ initiatives such as the annual ‘Visit My Mosque’. Others contain photos and reports of visits from distinguished guests including local/national politicians or other prominent personalities. For instance, the website of Finsbury Park Mosque has the phrase ‘fostering community and social development’ as its strapline, and its homepage carries reports and images from numerous varied advocacy and campaigning initiatives it has been involved in. These include collaborations with nearby Arsenal Football Club, Islington Council, interfaith bodies and charities among others.

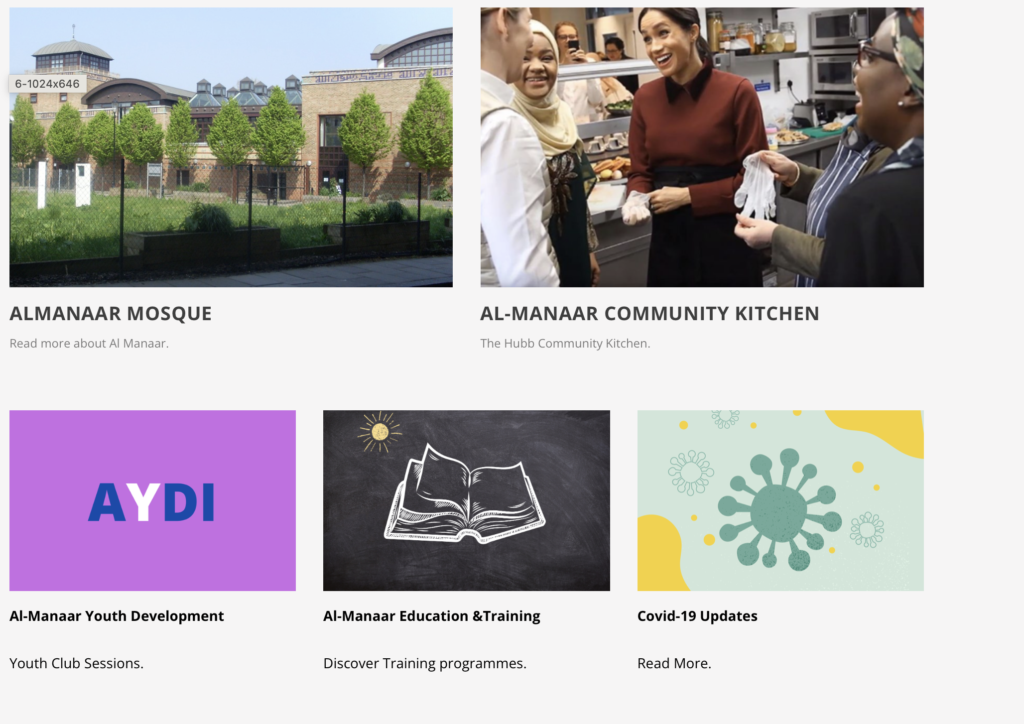

Several large mosques give extensive space to covering social support networks and projects. For instance, Al-Manaar in North Kensington has been heavily involved in supporting its local community during and since the Grenfell Tower disaster in 2017, and this is reflected in the content of its website which publicises advocacy and support initiatives around this theme.

For larger mosque institutions, the range of web content is indicative of their place as much more than simply a place to pray and congregate – rather they are very intentionally ‘hubs’ for their communities and beyond. This role entails service provision, representation and advocacy, and as such, a significant amount of web content is by its nature intended for an audience wider than the mosque’s immediate congregation.

Looking at the websites of smaller mosques, and considering their content in conjunction with our interview and focus group data, we can deduce that perhaps in terms of regular congregants, a website may be of secondary importance, when it comes to engagement with the mosque. It seems fair to say that unlike perhaps some of the other categories in this archive, a limited or inactive web-presence only tells a partial story and it would be inaccurate to assume that online content is wholly indicative of a (smaller) mosque’s activity.

Often the nature of small mosque organisations is that they are embedded in their local communities, and everyday features and activities are tied to a physical premises, relying on in-person communication or the relaying of information through less formal/more personal online channels. Many of our research participants cited WhatsApp and Telegram groups as a key source of information and communication with their local mosque organisations – and indeed, we found in our own data gathering that dissemination via such channels significantly opened up interaction and participation. There is a flexibility with this type of messaging as it is most easily accessible via smartphones or handheld devices. It also offers a range of degrees of anonymity and interaction. Many organisations utilise the ‘announcements’ or ‘broadcast’ function – whereby phone numbers and names of participants can be kept private and only viewable by group administrators. Similarly, only one-way messaging (from admins to all participants) can be enabled. For less formality, and greater engagement – messaging can be enabled for all participants. This is not to mention the ease with which a range of media formats can be easily shared and discussed.

This contrasts with the websites of national-level bodies or organisations and also those of collectives that operate mainly as online networks. These sites are generally much more intentionally curated in their content and presentation, acting somewhat as prospectuses, showcasing the activities of their mosque or organisation to a general public, but also specifically to partners (current and potential) and other interlocutors. For such websites, the online acts as a space of record – for documentation and archiving but also for engagement and collaborations. They are optimised for ease of browsing and to appear in search engines, and content is often updated and maintained more regularly.

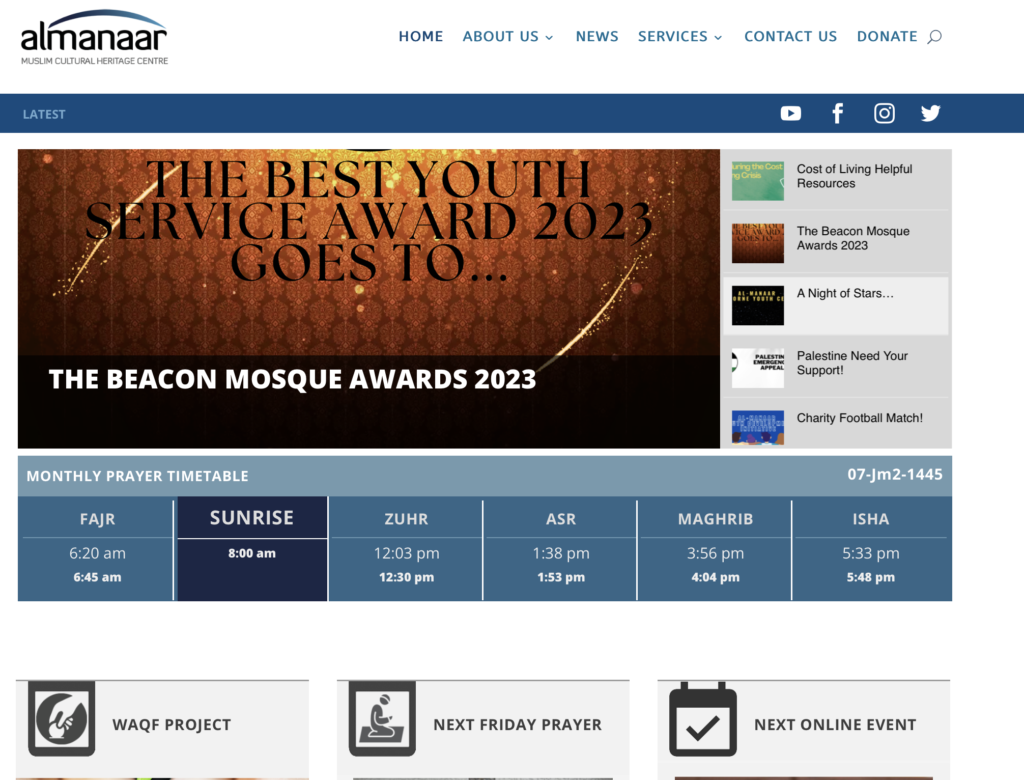

Notwithstanding that messaging and public profile are key elements of a large mosque/mosque organisation’s website – a ubiquitous feature of every website that we profile in this list is the local prayer timetable. It is notable that though perhaps this feature might be perceived as mundane and everyday, several of our participants described how they would check their mosque website for prayer times several times a day.

This archive collection is a work in progress. We intend to expand our analysis and content tagging in due course, connecting different aspects of the project. We will make further inroads into collecting and drilling down on content as Digital British Islam progresses.