This introductory discussion relates to the Charities collection in the Digital British Islam web archive:

Muslim charities have come to use the digital space extensively over the past couple of decades, particularly diversifying their use in recent years. In the early 2000s, the main Muslim charities had websites as place-holding portals with general project and contact information. A majority of charitable fundraising and community outreach relied on in-person presence in community spaces, such as mosques and other institutions, as well as fundraising drives at events or specifically organised campaigns. Paper fundraising leaflets and reports to donors were a widespread method of communication – posted to home addresses or distributed at community venues.

Since then, and in step with the charitable sector as a whole, we have seen a shift towards the digital that has gained immense momentum in recent years. Sophisticated fundraising platforms and donation options are one example of this. Most charity websites now have easily navigable donation forms which calculate zakah and offer gift aid options. With donor convenience now a high priority, platforms dedicated towards making donations easier and more effective have been developed, with growing popularity, as well as some unease. My Ten Nights is one such example. It works with fundraisers to offer donors the opportunity to commit to an automated donation scheme – whereby they sign up to a specified donation amount being released to their chosen charity on set dates. The name comes from the last ten nights of Ramadan, believed to be nights when good deeds are exceptionally highly rewarded, and thus when charitable giving his highly recommended. The philosophy behind My Ten Nights, along with other platforms employing crowdfunding concepts[1] aligns with a corporatist approach where maximising efficiency and material productivity (in this case, funds raised) is of prime concern. For this reason, they have attracted some critique.

The National Zakat Foundation website is an example of a page which offers a great deal more than the typical donor information, fundraising and project updates that are generally found on all charity websites. NZF offers a range of different tools, such as zakah calculators, a will-writing assistant, FAQs and a ‘knowledge bank’ with resources and short, accessible explainers written by experts.

A number of charities now work closely with influencers and content creators, a method of relatable and interactive fundraising with proven success. Penny Appeal is one such example – launching with a memorable and recognisable hashtag, #teamorange, it emphasises the scope for personal fundraising initiatives by groups or individuals. It promotes it fundraising through featuring influencers in comedy tours, a pantomime and other eye-catching promotional exercises such as its ‘Kid CEO’ initiative.

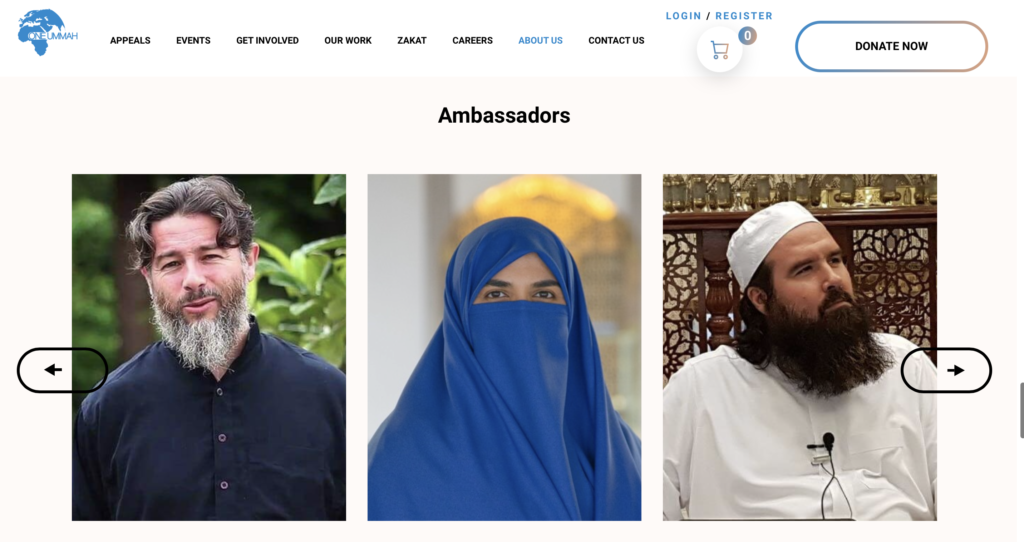

A growing number of other charities acquire endorsements from public figures for their campaigns, utilising the extensive reach of these individuals’ social media platforms to reach large audiences, as well as the credibility of scholarly credentials of religious authorities who can lend their voices to support specific appeals and projects. Their access to these public figures’ audiences is crucial for campaign building, and often the prospect of being somehow associated with influential public figures or celebrities is an element of appeal as well.

A final observation relates to the power of social media and viral campaigns: small, volunteer-initiated fundraising projects such as The Cake Campaign and The Date Project. These began as localised initiatives, often ad hoc efforts by volunteers to do ‘something’ to fundraise for a specific cause (in both of these examples, Syria). After experiencing viral popularity and success (in no small part due to social media), these projects became established, recognisable brands in themselves, particularly anticipated during Ramadan, the peak time of charitable giving for Muslim communities. Perhaps these are an apt illustration of how the digital has precipitated real transformations in how Muslim charities operate – a much changed landscape from the days when pamphlets and in-person fundraisers were the mainstay.

[1] www.launchgood.com is one such example. Although this is a US based platform, it is widely used in the UK and by UK charities. Others include www.GiveBrite.com and www.MuslimGiving.org.