The Medicine, Mental Health and Alternative Therapies collection on the Digital British Islam archive presents websites related largely to health and wellbeing. They can be broadly categorised into those aimed at Muslim practitioners and those aimed at Muslim patients. Types of websites covered include networks of Muslim practitioners, the most well-known of these being the British Islamic Medical Association (BIMA), directories of Muslim professionals, and treatment or support services. There is a particular focus on mental health in the websites in this collection including networks or directories of mental health practitioners (e.g. MCAPN) and mental health services tailored towards Muslim communities (e.g. The Lantern Initiative, Inspirited Minds). Additionally, the collection includes organisations offering therapeutic interventions that have a specific precedents in the Islamic tradition. These include treatments like cupping, or hijama in Arabic (e.g. London Hijama Clinic), ruqya, a form of spiritual healing (e.g. Ruqyah Central) and so-called ‘prophetic medicine’ , also known as tibb in Arabic, a form of herbal medicine focused on attaining balance in the body (e.g. Mohsin Health).

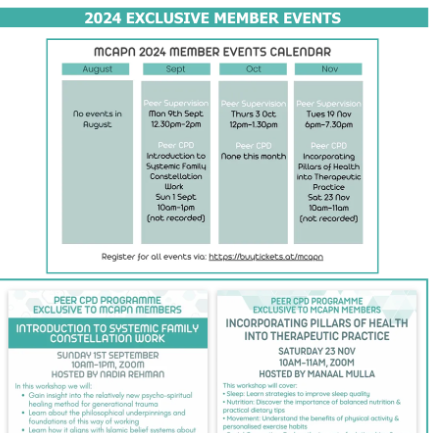

The relatively small selection of websites highlighted in this archive collection nonetheless suggests the wide range of health-related services and support available for both Muslim patients and practitioners. These range from public health campaigns aimed at Muslims (e.g. BIMA’s community health days), CPD opportunities for practitioners (see screenshot from MCAPN website below), and treatments for Muslim patients including hijama and mental health therapies.

Screenshot: https://www.mcapn.co.uk/ captured 23/09/2024

While the archive is not numerically representative, this collection highlights several mental health organisations catered towards Muslims. It has long been recognised that mainstream UK health services do not adequately cater for Muslim patients, with a new report highlighting Muslims feel their faith is ignored or viewed negatively by practitioners (Hekmoun and Abrar 2024). Many of the organisations in this archive collection have apparently been set up as a result of such issues, as highlighted by Inspirited Mind’s website which states:

“Our initial research showed many Muslims found it difficult to seek help as they felt they would not be understood by someone who did not understand their faith or culture, thus they chose to remain quiet and not seek help. We are here to change this and cater for this need.” (“Who We Are”, Inspirited Minds, accessed 23/09/2024)

The internet – including social media accounts run by such groups – likely provides an accessible way for many patients to engage with such services which are not part of mainstream NHS provision.

While accessibility is an advantage of online platforms, a drawback is that it can be difficult to assess the size and reputability of organisations from the perspective of patients/service users. Indeed, setting up website or social media account can be a key way of establishing an organisation before it has had much ‘real-world’ activity. I was initially involved in the setting up of MCAPN, for example, and remember that one of the first things done was to set up a website. The Muslim Therapist website on the archive is another interesting example. This seems to be a counselling service run by a single practitioner. It is possible that setting up a website and giving it an organisation-style name helps cement its place (at least online) as an available service.

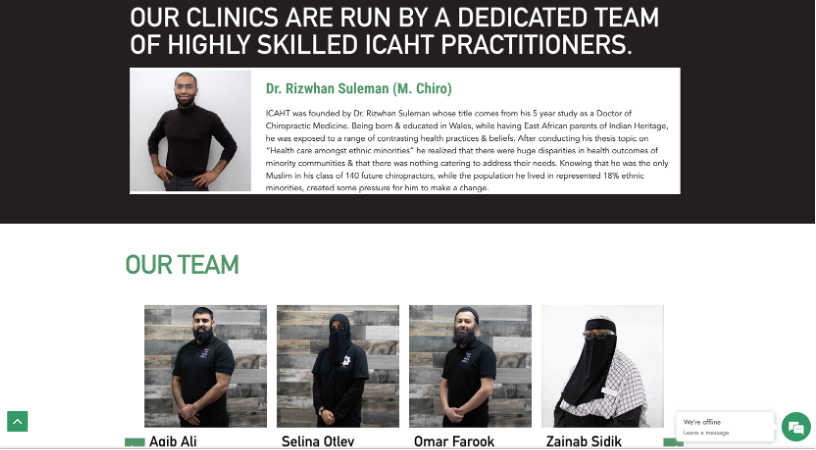

Websites and social media also do not give a clear sense of how many people are involved in a particular organisation. While some sites in the collection include a page outlining team members (see ICAHT screenshot below), they do not necessarily highlight all those involved nor the extent of their involvement. On other websites, such as BIMA, there is no clear list of members or executives with the relevant page of the site incomplete as of 26/09/2024. Speaking to medical acquaintances however, I have the impression that BIMA is a large network with UK-wide engagement and their reputation perhaps lies more in their in-person activity or non-website based interactions (including social media). The lack of individual contacts on some of these sites, especially those aimed at providing therapies, may have the disadvantage of making them come across as impersonal for patients seeking sensitive support.

Screenshot: https://www.icaht.co.uk/our-teams/ captured 23/09/2024

This difficulty in perceiving the size and reputation of organisations via websites and social media accounts is applicable to other collections in the archive and digital platforms more broadly. It highlights the ever-present risks of depending on digital media as sources of information. This is relevant to the broad spectrum of work encompassed in the Digital British Islam project recognising that what is displayed online does not necessarily represent ‘real-world’ activity. Such conclusions about the digital world link to Baudrillard’s discussion of the increasing blurring between the ‘real’ and the ‘representation’ in his concepts of “hyperreality” and “simulacra” (Baudrillard 1994 [1981]).

It is worth remembering that this collection has not included individuals and organisations who are active on social media but do not have a website (e.g. Muslim Doctors Cymru (https://www.instagram.com/muslimdoccymru/)) and those that have no online presence at all. We will explore this collection and others in more depth through the course of the Digital British Islam project. We are open to suggestions of websites to add to the archive and you are welcome to contact us with further ideas.

References:

Baudrillard, J. 1994 [1981]. Simulacra and Simulation. USA: The University of Michigan Press.

Hekmoun, J. and Abrar, S. 2024. Faith in Mental Health. Woolf Institute. Available at: https://www.woolf.cam.ac.uk/research/publications/reports/faith-in-mental-health. Accessed: 26 September 2024.